As usual, the King of Knots and Corners was busy in his tower workshop, bare-chested, bending a long glass tube into a glowing spiral. He was covered in lightning bugs, and the darkling stone bricks of the keep behind him glittered in luciferic pulses like the constellations. Sweat poured from his grey locks and collarbone, steaming from his callused hands and his burning fixture.

The King’s Treasurer quivered in the anteroom, slurping root tea and kicking the legs of his writing desk in a rhythmic four-beat measure. Thump-pop, thump-pop, thump-pop, thump. He wrote resignation after resignation after resignation, tearing his failures into parchment crumbs which gathered around his clogs like swatted insects.

The emissary from the Stick District rested his curly blond head against the plank door, staring into the tower at the King through its peephole. His hand convulsed around the doorknob. It took him three false starts before he found the courage to interrupt His Majesty.

“I have brought a message for you, my King,” said the septic youth, swinging open the door and simultaneously falling to one knee.

The King didn’t even look up. He was hunkered down in a pretzel, using both of his horny feet as leverage to corkscrew a length of purple pipe.

“Who are you?” he asked softly.

“I am a messenger,” said the smooth-chinned waif. A pair of lightning bugs landed on either side of his nose and flashed in forceful, asynchronous waltz pulses.

“The females eat the males,” said the King. “Watch out.”

The emissary brushed his nose nervously and slunk along the wall.

“So who do you represent?” asked the King.

“I am here on behalf of the Stick District.”

“What is the Stick District?”

“We gather sticks for trade and craft.”

“Please,” said the King, standing and wiping sweat from his body with a stiffened royal chamois, “Elaborate.” He tossed the towel and his most recently tortured bit of glasswork into a pile with the others.

“Sticks can become kindling. Or poles to toast sausage. Many of our sticks find their way into the thatch of houses and the floors of bars. We also make clocks, birdhouses, reproductions of the Chapel of Tears, brooms, artificial limbs, spider homunculi, and matches.”

“Fine,” said the King. “I believe you. What’s your name?”

“William, sire. Willy.”

“So what is your message, Willy?”

“It’s very short,” said the messenger, blushing.

“Good.”

“Maybe I should just write it down and leave it, actually…”

“Talk. Or leave.”

“It’s nearly incidental.”

“Please. I am very busy.”

“Well, it’s like this.” Willy took a deep, shuddering breath. “Your kingdom has fallen apart.”

“Pardon?”

“It’s bankrupt. You probably aren’t even King anymore,” said the youth, furrowing his eyebrows.

“What?”

“It has been months since you have been able to finance this kingdom. The coffers are empty. I mean, there are fifty warlords out there with more money and power. Anyway, the law is dead. Nobody wanted to tell you for fear of what you might do to them, but the local constable has been increasingly dishonorable toward my sister, so I volunteered. Everybody says there’s nothing you can do, but I wonder. You are still King of Knots and Corners. Who can take that away?”

“I am not hearing this,” said the King. “Get out of here.”

The King collapsed into the wooden chair that functioned as the tower’s lone piece of furniture. Glass snapped underneath him and skittered across the floor in a kaleidoscopic neon spray. The King didn’t seem to feel it.

“We all still respect you. My Lord. It’s just…we thought you should know. Most of us are still loyal. Many of us.”

The King picked up one of his spirals from the ground and considered it. He held it up to the tower window and matched it to the set of stars it represented on a giant sky map. Suddenly, he threw the structure to the floor (it bounced and held) and jumped to his feet. He grabbed Willy by his right arm and hauled him into the anteroom. The King’s Treasurer yelped and fell backwards out of his chair.

“Is this true?” shouted the King.

“It is true,” whispered the Treasurer from the ground. “Your staff is all gone -- or hadn’t you noticed? We can no longer afford to run the hospitals or the brothels, and the roller-coasters have all been dismantled and burned for firewood. Many of the poorest starved to death over the winter without grain and hot dogs from the public stores. I haven’t even paid myself in a quarter. My family begs me to quit. To become a full-time key maker.”

“You are quitting?” roared the King.

“I got my degree in key making from your Royal College of Arts and Letters. Your Royal College of Arts and Letters is now the barracks for a gang called the Squids. They drink poisoned oats together and turn their blood black as ink. Then they round up elderly pensioners and burn them in the public square. They charge a fee for watching. People pay.”

“This is ludicrous,” said the King, grabbing the Treasurer by his left arm and yanking him to his feet. “Show me my kingdom.”

The King frog-marched both of his subjects down the tower stairs, bouncing his Treasurer against the banister with every turn. He kicked through the hidden hole in the basement floor and peered inside. Where there had once been heaping piles of gold and jewels, now there was nothing. The King whirled them out of the tower and into the courtyard.

The three men stood there in the crunching leaves of fall. The pepper trees were not quite dead. But they were certainly empty.

“Where?” asked the King.

“Anywhere,” said Willy. “Forward.”

They marched forward. They marched through the Apple Gate and the King noted, with a sinking gut, that every single silver apple had been pulled with violence from the twisted yarn. The gate had the pock-marked appearance of a surly seventeen year old. There had once been a time when it was the bejeweled pride (and insurance) of the entire province.

Beyond the Apple Gate, there were itinerant camps as far as the King could see. A woman with braided yellow hair and circles painted on the knobs of her cheeks was sitting in a lawn chair beside a roaring gasoline fire. The fire was burning high in a rusted-out iced tea dispenser.

When she saw the three men push through the gate, she stood up and pulled her high rainbow socks up tight around her thighs.

“Why hello, lads! Looking for a bit of a roll? Bit of a suck?”

“No, thank you,” said the Treasurer, trying to avoid the aggression of eye contact. “We are not interested.”

The King just looked at her, dumbfounded.

“Of course you’re interested!” said the woman, kneeling down in the lawn chair and popping it up behind her. “This is prime stuff here. I can do you separate or I can do you together. I’m Ambidextrous Annie, so I am!”

Ambidextrous Annie fell back in her chair and pulled her long legs and stockinged feet up around her ears. Her toes were as long as chessboard bishops. She wiggled them and then curled them up with prehensile cunning, making moony eyes and smacking her lips.

“Stop this at once!” roared the King. “I am your lord and liege!”

“Sure you are,” said Ambidextrous Annie. “You can be my lord all night. All three of you can be my lord. One an hour. You haven’t got a bit of fish on you, have you? I am aching for a cod or a roe.”

“I am the King of Knots and Corners! THE King!”

“That’s a bit hard to swallow without breaking character for me,” said Annie. “I’m not really into fucking the dead. Not really much of a fantasy. But I’ll do it for a haddock. Sure.”

“I am not dead. I am your king,” said the King sulkily.

The Treasurer put his arms around the King and steered him away behind a hut. Willy followed reluctantly, peering at Ambidextrous Annie as she bent down in front of her fire to rake coals.

“The view ain’t free, boy,” said Annie harshly. “Lessen your pockets is filled with fry-up.”

Willy averted his eyes with a lightning wince and joined the others. The king had crumpled to the ground, a look of incomprehension and dread skeined sideways across his brow like the prow of a capsizing galleon.

“It is a corner,” said the King with a majestic sigh. “A deep corner. Four tight walls.”

The view on the other side of the hut was out and out dismal. The Treasurer wished he knew what to say. Once there had been a vizier who always had the right words, and a jester, and a court full of giggling idiots. But they had disappeared along with the gold and the sun.

Beyond the crook of the hut, a group of old naked men were sitting on a spongy airplane wing and watching a group of young naked men load sacks full of dirty carrots into a wagon with pitchforks. The sky was split down the middle by a jagged black cloud, and the horizon shimmered with the grey smoke of limitless foundries and factories. These pits were new. What did they build?

Where once had stood the King’s royal row of artisans and sages, there were now only ruined husks. The line of beautiful buildings had once stretched like an emerald necklace all the way to the Chapel of Tears. Now they looked like rotten gums, cracked from the brutality of their broken teeth. They were bleeding calcium stumps; tainted with the untreatable infection of desperate people in desperate circumstances. Even the Chapel of Tears, an indestructible building carved and dried from the carcass of a yellow whale that had brought the King’s people to this land in its belly, was sunken into a deflated lump. No incense rose from the blowhole in supplication to the gods of under and above. The pair of steel mesh cages which functioned as its doors hung wide open on sprung hinges, displaying unadulterated emptiness. There weren’t even any nesting birds or shivering dogs to worship inside its lifeless heart.

It was the King’s heart. It was a message from the world to his soul; from his gut to his head.

And it was loud enough to drive him speechless.

“You won’t get very far on carrots, bucks,” said one blind old man to the naked workers with pitchforks.

“Carrots is all we have,” said a youth.

“Where are you going?” asked the Treasurer.

“Away,” said the youth. “Somewhere we can respect ourselves.”

“To hell, if we can find it,” said another, wiping the sweat from his brow with the hairy back of his own forearm.

“I suggest double pants and gauze for the travel,” cackled the blind old man. “The constant trickle down the back of your legs will be orange as tiger skin, and the smell of bloody carrots will haunt you like the ghost of my amputated eyes.”

“No pants, old man. No nothing. We are just as bad off as you.”

“It’s not so bad. Not so bad at all,” said the old man, sniffing the air and turning his head slowly to face the three new arrivals. “Isn’t that right, oh my King?”

The group of youths whirled to face the group from the castle.

“King!” shouted the naked youths. “Impossible!”

“I have always been able to smell kings,” said the old man.

“What do they smell like?” asked one of the other sack-skinned irregulars.

“Nothing,” said the old man. “They smell like nothing at all.”

“The old man speaks true,” said Willy.

“I don’t know if I qualify any longer,” said the King with a growl. “I knew there were problems, but I had no idea. I have failed my people and my kingdom. I am no king. I am shit.”

“Shit!” said the old man, brightening. “I know shit. Look around! The shit has gotten so high that shit is all we can see. We can barely move one arm. Each breath is shit. Each taste of food is coated in shit. Our sex is shit sex. Our shit itself impacts; like rocks hitting rocks.”

The others grunted their agreement.

“But I have always been optimistic,” continued the old man. “Why? Because I have been shit on before, and the thing about being shit on, is that eventually the world shits out a shovel and the shovel hits you fat on the head. Sometimes it knocks you out. But when you wake up, you’ve got a choice: you can either drown, or start digging. You are not a failure, King of Knots and Corners. You are not shit. You are a shovel. And you are right on time.”

The King stared at the old man. He looked at the Chapel of Tears, where he was coronated nearly six decades ago in a forgotten ritual of blood and smoke. He groaned, he spat, and then he stood up.

“There are options,” said the Treasurer. “We could fight. We could steal. I don’t want to be a key maker.”

“I am tired of holding my sister every night while she shivers and cries,” said Willy. “I will murder for you, if you ask. I have a list. A long one.”

The King walked over to the blind old vulture and shook his hand. The old man laughed crispy carcinogenic bleats from his sunken and mottled chest. The King turned and faced the rest of his subjects. He cracked his neck.

“I have already made my decision,” said the King. “I must go into the Jawhole Downs and negotiate with She Who Sits. I will leave immediately. If I do not return, consider yourself a democracy. I suggest burning this whole place to the ground and starting over.”

The silence was absolute. Several of the shoveling men dropped their pitchforks. By the time anyone could speak, the King was already gone.

Everybody knew that you didn’t go into the Jawhole Downs. Not unless you were a fucking lunatic.

It wasn’t that nobody came back, although that happened more often than not. It was what the Downs did to those who challenged it. Those who returned, bloody and beaten and clutching sacks of iron or silver, were changed forever by things they never spoke of. They would whisper to each other in dark alleys or while prone under the tables in fetid bars beside the beer puddles, peanut husks, and condom wrappers. They spoke to no one else. They barely moved.

Every single one of them came back blind. And crazy as fucking oil slick rainbows. And missing exactly two limbs – either both arms, both legs, or one of each. But there was a trade: some were able to finally feed their families, pay off debts, or finance forgotten dreams. It was the most desperate thing one could do. Knowing the risks, knowing that to go into the Jawhole Downs and try to negotiate with She Who Sits would cost the greater percentage of everything, nearly once a month someone would choose the dark bargain and draw to the inside straight. It was a bad decision.

And the King was about to go down and negotiate for an entire kingdom.

Up in his tower, the King prepared a zip-lock leather satchel with what he would need. He took down two heaping jars of fireflies from his breeding tanks, one of each sex. His tanks, with their snake hoses and carcass sluices, sat like cellophane busts on stone shelves in his tower workshop, buzzing with fluorescent dream electricity. He put his hand on each tank and bid them goodbye. These were his iridescent children – the only hearts he had seen fit to nurture in his quiet dotage. It was unlikely that he would ever see them again.

He packed meals for himself. Tortillas filled with sausage, black beans, and chunks of red avocado. Delicately, he wrapped them in ice cold paper towels and fitted them into individual pockets of his satchel. He packed his scalpel, furlongs of good rope, and several changes of socks and underwear. He packed his high shoes and his low shoes. A dense novel to put him to sleep and then a scrappy, slender novel to wake him back up. A bedbag. A water bottle. Finally, he picked out his finest constellation – the Blue Carnival – a labyrinth of light and glass, turning and joining at seven elbows of cobalt radiance, a small intestine of translucent brilliance. The Blue Carnival held the King’s birth star, and, as had been prophesied by a long dead sage, his death star.

Wrapped, packed, and ready, the King climbed down the tower steps and made his way out the back. He shivered in the cold sun, hefted his pack and tightened it, and set off for the Downs. The Chapel of Tears and his tower behind him stretched out in a line like a rope hanging down into a bottomless void.

Willy caught up with the King on the road.

“I’m going with you,” said Willy. “We will face her together.”

The King snorted.

“You are not serious.”

“Sure I am!” said Willy, curling his fists at his side, his eyes blazing in newfound adoration.

The King debated silently with himself. He stretched his finger into the sky.

“But the stars, Willy…what do the stars say?” asked the King, quietly.

“It is day time, my King,” said Willy, puzzled, looking behind his shoulder to where the King pointed, resolute, like a hound dog or the central silhouette in a gas station mural. “What stars?”

The King punched Willy hard in the back of the head. Willy whirled around, fuzzy fury in his eyes, and then the King caught him as he fell unconscious to the scrub. The King laid him gently in the grass, making sure Willy’s new pink contusion at the stem of his skull was elevated and the ground underneath him was clear of rocks. Then the King continued south down along the path carved by the heavy steps and heavy tears of the effectively suicidal.

The Downs were not far. By sunset, the soil had already turned chalky and brittle, and white striations in the rising cliff edges paralleled the horizon. The King had never been out before in this direction, but he had no fear of losing his way. He felt pulled, inexorably, to the hole at the end of the path like water searching for the gutter as it sliced through horse dung and ran between the fingers of distracted children.

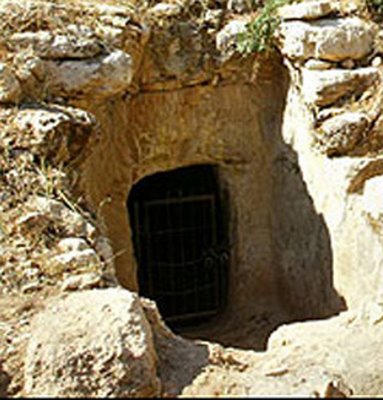

By midnight, he had found the locus of the Downs, and stood staring at the chiseled chalk steps that led deep into the earth like a crack in couch cushions. There were bones and clothes and crumpled sheets of foolscap littering the gully in small, sorted piles. Several glassy pools of dried vomit indicated that not everybody went down these steps with a heart of stone and a head of fire. The King removed a cone of rocks from a piece of parchment and read it to himself. There was an anatomical drawing of a human heart done in black charcoal and written over it raggedly was this cryptic warning: “YOUR CARRY-ON BAGGAGE MUST FIT INSIDE THIS COMPARTMENT IF YOU WISH TO FLY.” Lunacy.

The King ate one of his tortillas, contemplating the lightless hole before him. He read a little bit by moonlight from the thin novel he had packed, letting his mind slow down to a crawl like the rotors of a ceiling fan. When he felt calm enough, he fitted the canisters of fireflies into the Blue Carnival, tumbled it until it sparked, wrapped it around one arm, and then slowly descended into the fungal, fecal puncture.

2.

There are some places in the world that are better off dark, realized the King with a sudden stab.

The tunnel under the Jawhole Downs was coated in blood the way a striped drugstore straw gets coated in thick strawberry milkshake. There were bits of gore smashed into the rock sheet like pits of berry. Handprints of all shapes and sizes decorated the walls from where those who had gone in without torches had stumbled on their way down and made their mark. Some of the blood looked fresh under the King’s flickering blue light, as if parts of the tunnel were painted daily to keep the unfinished fresco wet.

The tunnel was cramped shut like a fissure in a closed fist. The King had to make himself a grain of sand to squeeze through, tightening his shoulders and lowering his bull-neck underneath his clavicle like a rhinoceros. The tunnel led down for a good fifty yards before leveling out and leading back up again. It widened and shrunk with cardiac regularity, boulders bulging in the walls at heartbeat intervals. The King felt like a blood vessel pumping through a runner’s knee, careening off every two-bit ventricle and capillary.

After an hour of walking, the King started to hear the rushing sound of water. Not long afterwards, he came to a join in the tunnel where water poured down from the rock ceiling in a clear sheet, down past the tunnel into a crack in the ground that appeared to be without bottom. The waterfall formed a liquid portal, and in the blue light of the Carnival the portal had the unsettling appearance of an indigo spit-bubble forming on the frozen lips of an overworked ice horse. It was impossible to see beyond it.

The King unslung his bag and grabbed it tightly to his stomach, bending full over at the waist to form a rain-fly with his back. Tapping the glass with the nail of his index finger and listening to the resonance, he made sure all of the valves up and down the Carnival were completely sealed. Then, with a sigh of resignation, he made himself as small as possible and backed into the waterfall, trying to move quickly without losing his footing in the powerful spill.

The solid sheet of water soaked him from ass to crown. However, by going backwards, he managed to avoid splashback from underneath, and his package was only minimally soaked. The Blue Carnival lost none of its sheen, and the King realized that he was probably the first person to make it through this section of the Downs without losing his light.

Sure enough, directly beyond the waterfall was a haphazard arbor of a castaway torches and rags. Each was charred and gutted, and many were broken in half out of apparent frustration. The King’s fireflies were rattled from the falling water, and the King cooed at them in a soothing falsetto. He stroked their tubes until they settled along the edges, and then he wiped the pipe down carefully with the still-dry cuffs of his pants.

Beyond the waterfall, the tunnel widened considerably and the blood on the walls was replaced by spongy grey lichens. They grew in infant clusters like wagon wheels, and at the center of each outcropping was a leaf-like structure with spiny nubbins that, when the King twanged them, proved to be both as sharp as they looked and more unyielding. They looked like little bottles. The King looked closer. Beaded at the tip of each spine was a drop of thick lavender pus. These secretions had dried in runnels down the walls between the lichens like varicose veins.

The King thoughtfully took one of these thorns between his fingers and squeezed. The purple gunk oozed out sickly, not quite chunky enough to fall. The King cut three thorns from the wall with his scalpel and buried the ends inside bits of sausage to avoid accidentally pricking himself. Ooze honeycombed the inside of each fungal nub like the filling of a jelly donut. The King wrapped his prizes in a strip of satin torn from his bedbag and pocketed them. Very curious.

Stopping only to change clothes and to have another bite to eat, the King continued on his way.

He did not have much further to go. After another five minutes of picking carefully through the tunnel, avoiding the walls and taking extra time to move stealthily, the King found himself at the mouth of cavern like a tremendous turnip. All of the walls curved from the tunnel to meet at a thin granite ledge. The ledge held an enormous wooden door whose only distinctive characteristic was a glinting gold handle that turned and twisted like the first over-elaborate lie of a small child tired of being whipped.

The floor of the turnip-turned span was covered in pine shavings and shredded newspaper.

Any room without walls and what happened when walls met each other made the King nervous. This room was no exception. There was something malevolent about it. He was too eager to run to the door and throw it open to face his destiny beyond. Everything about the room pulled him toward the door, and he mistrusted the apparent lack of options.

He took out a coil of rope and tied it to the spine of the heaviest thing in his bag – Seven Decades of Chalk by Franklin the Writer. The back cover promised a detailed fictional account of the torrid life of a private teacher of advanced alchemical arcana and his spiritual journey from dross to steel. “Pregnant with prose as rich and satisfying as the baker’s daughter,” pronounced Gerber the Critic. After several years of pawing through it before bedtime, the King had only gotten to page 50, leaving the brunt of the book crisp, fresh, stiff, and strong. Perfect for a makeshift plumb-bob.

The King swung the backbreaking novel over his shoulder and let it fly into the center of the beveled chamber. It landed with a harmless kunk, punching down inside the shavings like a bucket full of lead-shot slamming into the meaty flank of a well-fed heifer.

So the room had a bottom after all. The King’s felt his hackles bend and wave along his neck like rows of corn. There was still something wrong.

The King started to slowly draw back the rope, cutting a churning scar in the flotsam. The book made a noise like a pot full of boiling grease as it dredged through the debris. The agitation spread. The shavings themselves started to churn madly. Edges of cartoons, want ads, editorials, columns, and crosswords bubbled into the air like tack beans on a skillet. The rope was seized by something powerful and yanked back and forth. The King tugged twice, and then the line went slack again.

Now we’re getting somewhere, thought the King.

He took a step further into the room and peered into the wreckage. There were definitely creatures in there. Thousands of them. All that was left of Seven Decades of Chalk was the title page and a diagram of the soul approaching union with pure reason by applying itself to the Ruby Grindstone of Pain.

The King snatched another length of rope from his bag and began lashing it into a crude net. Underneath his expert fingers, the rope nearly weaved itself together. Fiber swept into fiber with spontaneous precision in the same way Christmas lights pull together into an instant tangle the moment they are unwatched.

The King cast the net into the shreds and then pulled it tight. He wanted to see these wee beasties.

The creatures were the size and shape of a peach. At the butt of each peach, a full set of jagged teeth split the creatures in half. No eyes, no limbs – just fins like a fish. Some of them were covered in thick black hair, matted like the goatee of a drummer. Some of them were hairless and infected-looking, their bodies sticky with split craters of seething goo-filled gashes.

The King poked one of the hairy ones through the net with his scalpel. It leapt from the ground of the cave a foot high and then it popped inside out, its inner lining shooting through its gearbox-teeth like the stomach of a starfish. It gnashed on the ground, flipping back and forth like an eel on the deck of a boat. It had turned into one of the hairless, poxy ones. He poked it again. It popped back to its original, hairy form. The King smiled.

“Fine,” said the King. He made a noose out of rope, tossed it with surgical precision at the handle of the wooden door, caught it, and then tied the other end to the closest outcropping. He swung himself upside down around the rope like a bear climbing a tree branch and humped his way across the divide. He dropped to the ground on the ledge in front of the door, opened it, and then passed through.

It was the end of the line.

The terminal stop.

The brain at the end of the stick.

He had found the court of She Who Sits, and evidently, he was expected. He set down his pack and the Blue Carnival, and he shut the door behind him.

The court of She Who Sits was exceedingly well-lit – a welcome change from the dank and the dark. It was a vaulted steel chamber two stories high, with sharp ebony patterns decorating the deep blue walls. Sconces carved from the jawbones of extinct animals – something like a cross between a horse and a tequila monkey – jutted from the walls, their bright red lights overlapping in linked circles. In the center of the room, She Who Sits sat on her throne made of limbs -- bones, flesh, and mummified amputations lifting her high and cradling her in resplendent decay.

She was so young. She was so terribly beautiful. The back of her chair was built into a massive grandfather clock made of femurs. The only noise was its ticking.

Standing quietly next to her was a gaunt, middle aged man wearing a white button-down jumpsuit and a stethoscope. He was a giant – literally eight feet tall. The circles under his eyes were the color of pinched plums. He never blinked. Behind him was a long steel table with a thin sheet of paper rolled over the top. The floor was carved from one giant, impossible mirror. Gold and jewels were everywhere, blinking like traffic in the red jawbone lights.

“You are no peasant,” said She Who Sits.

“I am the King of Knots and Corners,” said the King. “I am here to bargain.”

“Ridiculous,” said her attendant in a cold, sneering gasp. “The King is a doddering idiot.” His syllables were clipped as short as his hair.

“Ridiculous,” said She Who Sits. “But true.”

She appraised the King coldly.

“You have not been pricked by the Wine Bottles, I see,” she said. “You are here with all of your mental faculties intact, meager as they may be.”

“You mean those lichens?” asked the King. “I had a light.”

“They make men crazy,” said the gaunt man. “They make them crazy with fear.”

The King frowned and put his hand in his pocket.

“So what are you here for?” asked She Who Sits. “What could a worthless monarch possibly want from a wretched exile?”

The King thought about this and then folded his arms.

“I want everything,” said the King. “I want everything you have. All your silver, gold, and jewels. All your paintings and sculptures and antique music boxes. I am taking it all back. Technically, you are my citizen, and I am here to collect back taxes. Consider this an audit.”

The attendant raised a pubic-thin eyebrow. She Who Sits said nothing.

“In return, you will be allowed to stay here in this hole for as long as you want,” continued the King. “My armies will not exterminate you as if you were a rabbit warren in a tomato patch. You will be allowed to continue your trade, although it is possible that word of your new bankruptcy will spread. You may not get so many visitors.”

She Who Sits allowed herself a thin smile.

“Armies!” she tittered. “Your kingdom can’t afford to pay a dogcatcher. If it weren’t for personal honor, and the thrill of the trade, I would have killed you already. To be short, your offer bores me.”

The King coughed.

“Those limbs are the limbs of my people,” said the King, pointing. “Your wealth is the wealth of my ancestors.”

“I was banished here so long ago that I barely believe the legend myself,” said She Who Sits. “The land was forced on me, but I accepted my prison with the purest resignation and defeat. The archeological wealth was a happy accident. And your citizens are more than happy to TRADE sight, sanity, and an arm and a leg for MY money. Especially lately. Perhaps other avenues of profiteering have been closed to them.”

She Who Sits leaned forward on her throne. She took a stone goblet from a clenched, rigor mortis-stiffened hand that stood crooked at her side and sipped from it.

“Perhaps through aristocratic negligence?”

The King bounced up on the balls of his feet and then eased back down.

“Well then – what’s your counter offer?” asked the King.

“It isn’t an offer,” said She Who Sits. “It is what will happen. You will lose your eyes, and your arms, and we will pinch together two parts of your brain never meant to meet. In return, you will be given a sack of copper gas-caps to take back home with you. Your eyes are greedy, your brain is without industry, and your limbs can no longer carry weight. Let it never be said that She Who Sits plays favorites. Put him on the table, Kellogg.”

She clapped her hands. The giant in the white coat snapped to attention and advanced on the King. Kellogg -- this towering cadaver -- pulled a length of leather from his sleeves and cracked it menacingly.

The King flicked the bits of sausage from the ends of the thorns in his pocket and fitted them inside three knuckles. He crouched as if terrified, and as soon as Kellogg was close enough, he struck. He caught him right in the side of the neck with the Wine Bottles, and then rolled out of the way as the attendant lost his footing. The thorns went deep, and Kellogg began to squeal like plastic cups being fed into a food processor.

“What did you do to him?” shrieked She Who Sits.

“Nothing special,” said the King.

The poison was fast acting. Within seconds, wine-colored froth formed on Kellogg’s lips and then began to spew from every orifice in his head – ears, mouth, nose, and eyes. Kellogg sprayed as if uncorked, running around in stiff circles with his hands high over his head. The King kicked opened the door to the turnip room, and then kicked Kellogg through it. Kellogg tripped on the ledge and then fell into the still-churning shavings.

The King quickly shut the door on the screams. Mercifully, they were few.

“When was the last time you negotiated with somebody who wasn’t crazy from your poison?” asked the King.

“It has been a long time,” sighed the seated witch.

“It’s a bad way to do business. Unsporting.”

“I never claimed to be sporting,” said She Who Sits.

“I will go ahead and take everything now,” said the King. “And let’s be quick about it.”

She Who Sits merely stared at him, sipping from her goblet and flaring her nostrils.

“We will make a new deal,” said She Who Sits, shifting her position. “The last person to overpower a consort was Kellogg, and you have killed him. He was talented, but lacked imagination. And passion. He was very poor conversation, and a very poor lover. I do not miss him. Why should I?”

She grinned.

“You will take his place.”

“Impossible,” said the King. “Who will take the treasure back to my people?”

“You will try,” said She Who Sits. “Go ahead.”

“Promise me my Kingdom will be rich again,” said the King.

“I can promise you that,” said She Who Sits. “I can also promise that you will never leave here. You will find new delights in my arms. In my skin. There is much that can be done sitting down.”

The King snarled and began filling his pack with gold. She Who Sits fingered the stays on her corset and smiled coyly. She was done making deals with peasants. She had traded up. Let the Kingdom have her darkest treasures, she thought. Perhaps She Who Sits had finally found someone she could stand for.

3.

As the King of Knots and Corners made his way back through the Jawhole Downs, his mind reeled. Something was happening to him. He did not feel as if he were traveling through a blood-soaked intestine – he felt in turns as if he were flying through outer space, as if he were carving his way through the densest tropical jungle, as if he were roaming the halls of a decadent picture gallery, replete with the most scandalous and alluring portraits of the darkest hells of human existence.

He could taste perfumes of wild, unchained imagination. He could feel the leaves brush his face as his scalpel became a machete and he hacked at man-eating flowers on his search for fallen temples. He could see the stars streak by as he approached light speed and punched through black hole, after black hole, after black hole.

His pack was no longer a satchel filled with jewels. It was a house made of peppermint, with dog feet for stilts, bending up and down on a mountain made of rain.

Dog paws pummeled his aching back, so he set the pack down and watched it scamper away.

He stumbled on a rock outcropping. The King was soaked to the bone from the Downs waterfall, but his brain was on fire. He felt it in his fingers. In his eyes. The rope of the world was becoming untangled, and his febrile heart leapt in his chest in new, devastating directions with each clonking footstep. Carried with his heart were his tongue and the corners of his bewitched soul.

“I have been tainted,” said the King between his teeth. “Ensnared.”

He moved forward. He was a detective hunting for new drugs in an apocalyptic city of the past, fighting gangs of criminal mystics with dead computers and ransacked technology. He became a card-sharp in a wooden death town, dealing his own hand into the hearts of every lady whose eye he could catch. He was a merciless pirate, executing savage justice on tribes of idiot pilgrims who worshipped him like an evil deity.

With a flash of clarity, he saw himself and tried to speak. To yell. To rage. But he could only make lies. He could only weave together the knots of the fictions that poured into his head seemingly against his will. He slapped a hand against his mouth. He had to escape. He had to get out of this pit before the pit ate him like a sandwich.

At the entrance to the Downs, Willy and Ambidextrous Annie were huddled underneath a blanket, waiting without hope. Annie’s fingers were greasy with fish batter. Willy’s head didn’t burn so bad anymore. He had discovered the world’s oldest painkiller.

“You know he ain’t coming back,” said Ambidextrous Annie.

“But he might,” said Willy.

“Even if he does, you know what it will be like.”

“If he doesn’t come back, then I am going in after him,” said Willy. “If he is crippled and crazy, then I will put him out of his misery.”

“Kings, brats, cats, and drunks,” sighed Annie, “The only thing they have in common is that you can’t tell them NOTHIN’ about NOTHIN.’”

Willy squinted into the gloom, ignoring what her feet were doing to his trousers.

“I see something!” he shouted, standing and raising his torch.

“Goblins? Chinese?”

“It is the King!” said Willy. “He’s alive!”

“How many fingers and toes?” asked Annie, thwarted, lying down in the dust.

“All of them!” said Willy. “But all empty.”

The King fell down on his face in the threshold of the hole with his hands stretching toward the light of Willy’s torch. The Blue Carnival exploded on the rocks, releasing swarms of fireflies that alighted on the King’s chest and head like crows on a hanging tree. Willy ran to him and tried to drag him out, but he wouldn’t budge. Annie crept over to them on her hands and knees, curious.

“Listen to me,” said the King in a strangled voice. He grabbed Willy by the shoulders and pulled him close. He whispered urgently in his ear for a solid twenty minutes. Then, as if he were a pail on a winch, he let Willy go and slunk slowly back down into the cave, lit up by his cloak of lightning bugs. His fiery eyes burned deep on Annie’s retinas, leaving bits of radioactive sand under her lids that she had to wipe clean before she could see again.

“What did he say?” she asked, pouncing on the stunned youth.

“It was…a story,” said Willy. “The plot of a story. He said he would be back tomorrow with another one. He sounded like he was choking to death. But the story! Jesus. I have to write it down immediately before I forget.”

“I don’t get it,” said Annie. “You can’t eat stories.”

“No,” said Willy slyly. “But you can sell them. There are kingdoms without. Stories are even better than sticks, I’ll wager. Every kingdom has sticks. I think we are supposed to make stories and sell them. I think we can be rich again. Jesus. I have to get to paper…”

Willy shook his head clear and started back up the path.

“Is he still our King?” asked Ambidextrous Annie.

“I don’t think so,” said Willy. “He said we didn’t need him anymore.”

“You didn’t put him out of his misery,” said Annie.

“He said he would be back. He said not to follow him. That no one should follow him, but that he would be here at sundown tomorrow -- and every day thereafter. He said he could never leave the Downs again. That his mind was tethered to it and would snap if he tried.”

They pondered this together.

“What was the story about?” asked Annie.

“The stars,” said Willy. “It was about the stars. And where dreams come from.”

2 comments:

Such a tired cliche, leaves crunching underfoot. In your 40th paragraph (appx.) you have chars standing in the crunching leaves. If they're just standing there, crunchy sounds won't last long. This crunching gravel/leaves cliche always reminds me of the high school english teacher imploring students to involve the other senses, have readers feel and smell and hear the action. I'm all for involving all senses, but use something else besides gravel crunching or leaves rustling.

I aim to finish reading this one, and to comment more....

Meanwhile, ahl be bach.

ok, lots more, all of it good.

overall, great story. I liked ambidextrous annie, how her toes curled like chessboard bishops. i like how you used a few but not too many good cool strange words, like vizier, runnels, etc.

starting with the para that begins "I have already made my decision..." that and the next 5 paras are simply great, replete with lines like "If I don't return, consider yourself a democracy" and "oil slick rainbows." simply great.

i like "The portal had the u.a. of an indigo spit-bubble on the frozen lips of an overworked ice horse." many similar nicely formed sentences abound in this story.

percentage of zingy quips or obviously thought-out lines that worked for me vs. didn't work ran at about 8 to 2 in this, with 8 working just fine. excellent piece of creative work; i don't really see this as representative of something going on somewhere, like is it a fable? doesn't matter; it's great. I LIKE IT that it leaves me scratching my head in some ways, yet everything that matters got resolved.

Post a Comment